Making of: Pest Control

This is a post about my game Pest Control.

If you haven’t played Pest Control yet, you should do that. If you need a mac port, contact me at blog [at] notfruit.net. I can’t make a mac port because I don’t have a mac to build on. But if you do, maybe you can make my mac port! Or I can send you instructions on how to build locally.

In this post I’ll be sharing what I remember about the development process. I’m writing this post the week the game came out so the memories are still fresh.

I divided this post into sections, here’s a table of contents to make it a bit more wieldy to navigate.

- Background

- Putting a team together

- Brainstorming

- “Player” AI

- Spawn Patterns

- The All Nighter

- 11th hour Playtest

- Takeaways

Background

You’re probably familiar with Game Maker’s Toolkit (GMTK). But just in case: it’s a YouTube channel with a massive following about game design with a focus on the developer’s perspective. Less “X game is great and here’s why” and more “how the developers of X game achieved Y, and how you can too.”

Every year since 2017, the GMTK Team put on a game jam. It started out as a humble “community game jam” like many we’ve seen before. Starting around 2019, GMTK had eclipsed Ludum Dare in number of submissions. The average Ludum Dare has about 2,400 submissions. GMTK 2019 had 2,562 submissions, and has only gone up since then, with the latest 2023 jam clocking in at a jaw dropping 6,877 submissions.

Making the top 100 in GMTK means your game rose to the top 99.5 percentile of submissions… if you care about those sort of things (cough, it’s me, I care).

Composer, friend, and extremely cool guy Ryan Yoshikami joined me in Ludum Dare in 2020. Our submission, Lay Down Your Roots, won 3rd place overall. Both Ryan and I refer to that time as when we “won” Ludum Dare.

That same year, we decided we had so much fun doing Ludum Dare that we decided to take on GMTK as well. That was the year that we made Three in a Rogue which I’ll talk about eventually. All you really need to know is: It didn’t go well. Ludum Dare is 24 hours longer than GMTK and scoping for a 72 hour game is very different than scoping for a 48 hour game. The game we submitted was an unplayable mess. I could summarize every comment on our submission page as “cool idea, but I barely made it out of the first room.”

The following year, in 2021, we made Function Conjunction which smashed into the top 100 at 46th overall. A bonus of hitting top 100 in GMTK is that Mark Brown, the voice and later the face of GMTK, will personally play your game and pick his top 20 favorites from the top 100 and feature them in a video reviewing the jam. He’ll also pepper in clips of other games that made top 100 in the preamble of the video.

As far as Ryan and I are concerned: getting featured in that video is the true “win condition” for GMTK Jam. We weren’t featured in 2021 as one of Mark’s favorites, but we were visible in the preamble for a whopping 3 seconds at the 0:57 mark of the video. Almost a win, so close.

In 2022, we completely blundered. Seven Pips hit an embarrassing 1087th place. I want to do an entire retrospective on Seven Pips, but this post is already getting long and I haven’t even started talking about Pest Control yet. So let’s do that.

Putting a team together

After the Seven Pips disaster, Ryan and I debriefed on the jam. I didn’t have a clear vision for the game so he didn’t have a clear reference point for the music. Our scope and ideas were limited to what I could create with procedural art, which was a recipe that worked for us in the successful Function Conjunction and the award winning Lay Down Your Roots. It was becoming clear that those were the exception and not the rule.

We agreed that the most actionable change for next time was: hire an artist. Fortunately GMTK has a teamfinder app specifically for the jam. You can plug in the skills your team has and the skills you’re seeking and then broadcast and respond to ads for prospective teammates.

The teamfinder app conveniently integrates with Discord. So if someone wants to “reply” to your teamfinder ad, they just shoot you a message. Meeting people this way is awkward. We ended up recruiting 2 artists this way and we fortunately ended up with cool, nice people but I was anxious about ending up with assholes or people who don’t respond well to criticism.

The first contact with prospective teammates is a skill I need to get better at. I should have been asking to see portfolios and vibe checking before I just let people in. There’s usually a huge influx of people looking for teams right at the very end. One of our artists joined our team literally 1 hour before the jam started.

Brainstorming

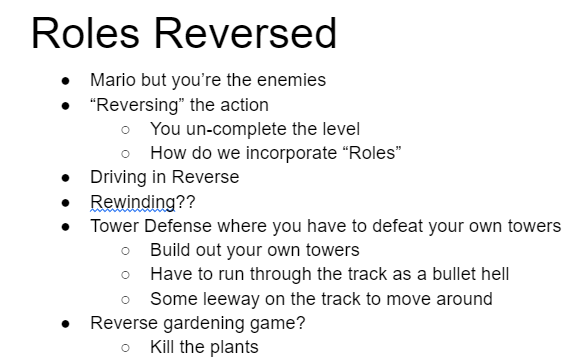

The theme was Roles Reversed. Right after the announcement, the four of us hopped in a group call to brainstorm ideas.

I have a system for brainstorming game jams. It looks something like this:

- Create a shared google doc that anyone can edit.

- Make a bulleted list of all the ideas people have for the theme.

- Every time anyone has any idea that isn’t already on the list, add it. Even if you personally hate it, add it to the list anyway and move on.

- Add sub bullet points if you have something to add to an idea.

I don’t think I contributed any top-level bullet point ideas. Maybe I’ve just done so many game jams that I’m just tapped out of “new game ideas.” I really benefitted from having extra voices in the room so I can build on someone else’s idea rather than starting from scratch.

Our first big idea was a tower defense game where you periodically swap roles with the enemies. I didn’t like this because it didn’t feel like the player gets a lot of agency playing as the enemy, most tower defenses have the enemies running through a strict maze. But this tower defense idea was a key ingredient in getting us to our final concept. A few bullet points down we wrote Game with 2 distinct roles, eg: "Towers" and "Mobs". This was an important articulation of what type of game we wanted to make, and the tower defense idea helped us find it.

I’m not sure what prompted it, but at one point Ryan said the phrase “Gradius versus Gradius,” someone suggested the idea of a game that logs your actions and then plays them back as the opponent. I liked that idea a lot!

From there, and with Gradius on the mind, we brainstormed the idea of a shoot ‘em up (aka shmup) with all the classic tropes: powerups, bombs, and killing waves of choreographed enemies. At first you play as the ship, fighting off waves of enemies. When you die, the game resets, and now you control the enemies, and the player ship is now controlled by a replay of your inputs in the previous round. Your goal is to spawn waves of enemies that your previous replay did not account for. Once that round ends you’d swap back to the player ship, fighting the new sequence of choreography you used to kill the last ship.

I had suggested that we just let you play as the enemies and let the player be AI controlled. At the time I thought I was cutting our scope in half, in retrospect, I think I did the opposite.

This was the first, and only, bullet point that got 4 layers deep in sub bullets, which is a good sign that we’re onto something good. Everyone was excited about this idea, so we kept digging.

Making the goal be “kill the player” felt too obvious. Instead, we wanted the game to be about finding a balance, almost killing the player, but not quite. We were putting the “real player” (as in, the human playing our submission) in the shoes of the designer. Trying to curate a well balanced experience for their virtual player, with different player “personas” that have different play styles and preferences.

We were picturing a Wreck-it-Ralph-style world where the game is orchestrated and directed in real time to appease whatever player is sitting at the cabinet. Enemies are essentially improv actors trying to put on the best possible show for the player. Meanwhile a producer behind the scenes gives you advice on how to improve “ratings.”

It was at this point that we had the idea for the “fake out” (my friend Jose later called it the “cold open”), where the “real player” isn’t given any information at first so they (most likely) assume the goal is to kill the player so they overload the board with enemies and kill the player. The producer then steps in and chastises you for overwhelming the player, teaching you how to play the game properly. I didn’t realize it at the time but this fake out is perfect for a game jam game. It’s typical for a jam game to drop you into the action right away because the team didn’t have time to make a title screen. In this game we drop you into the action as a slight misdirection before we introduce the game in earnest.

The artists decided all the visual thematic elements of the game within the game: The enemies should be insects and the player should be a fly trap. I didn’t find out about this until they sent me sprites of bugs and plants. I later read in the google doc the 2 sentence summary of lore they wrote: the fly trap had eaten the “king fly” and now the bug empire was striking back for vengeance. I loved it! It reminds me of working on Puppertrator where Kristin Mays suggested that all the characters in our mystery game should be anthropomorphized dogs.

“Player” AI

This section gets pretty technical, you start to glaze over, you might want to just skip to this section.

The two major technical hurdles for this game were the player AI and the enemy spawn patterns.

This was the first real AI system I had made since Krill or Be Krilled, and that was 2015, eight years ago. I had learned a lot since then, but I still wasn’t entirely sure I could make a compelling AI. I was, however, confident that I could make the enemy spawn patterns pretty easily, so I decided to take on the risky thing first.

I took the one lesson I learned from Krill or Be Krilled. No matter how the AI works, its output should simply be the thumbstick direction and whether or not the fire button is pressed.

Another smart decision I made early on is that the AI only occasionally re-evaluates its state. Once they chose an input, they’d hold that input for about 0.1-ish seconds before they re-evaluate and choose a new input. This meant that even if the AI had rules that made it play completely optimally, the poor “reaction time” meant that they would still sometimes get hit. This was one of the first tunable variables that factored into the player persona.

My first attempt looked like this. The AI has a “target enemy” it was interested in killing, moving to the nearest position it could find to line up a shot with that target enemy, and then changing targets when that enemy dies. This has a bunch of problems. This isn’t really how people play shmups. I play shmups dodging the bullets that are immediately near me, and trying to line myself up with where I’ll hit the most enemies.

For my second attempt, I wanted to be able to specify zones on the screen that the AI would consider “desirable” and zones the AI would consider “dangerous.” The AI should trend towards the area most desirable while avoiding any area marked dangerous.

I think an apt metaphor is smell. Every frame an enemy is on screen, it wafts a pleasant odor up to the top edge of the screen. The longer the enemy stays on screen, the stronger the scent gets. However closer to the enemy (and around the bullets the enemy fires) have a bad scent. A bad scent is not just a “negative good” smell, it’s a whole separate measure. A given spot can have a very positive odor and also have a very small stink.

Every time the player re-evaluates state (every 0.1-ish seconds), the player looks for the nicest smelling spot on the screen. If it can draw a straight line from its current position to there without intersecting any bad stink, it will choose it. The AI will tolerate a little bit of stink in order to get to its next spot. How much stink it’s willing to tolerate is another factor driven by player persona. If it gives up, it chooses the next best smelling spot. The AI also doesn’t like being actively inside a stink cloud. If it is, it’s first priority is to navigate out of it.

Each player persona also has a preferred “comfort zone” on the map that has a constant baseline pleasant smell. Meaning that all else being equal, the player will prefer to stay in their comfort zone. For most players, this zone is the top third of the screen. Some personas have a comfort zone that’s the size of the whole screen, causing them to play way more aggressively with just one small tweak!

Since smell clouds can build up over time, ships that have been on screen longer naturally tempt the player more. Bullets project a slight stink just ahead of where they are so the player can “anticipate” them and dodge out of the way.

That’s pretty much it! It took a bit of tuning to get the numbers right, but the result is a player that feels very reactive to whats going on around them despite the fact that the AI doesn’t even know what a “ship” is.

I played quite a few “reverse shoot em up” submissions to this jam. Partly to scope out the competition but also to see other directions we could have gone. I’m very proud of how our “player” behaves. Most people do a cyclic pattern or basic repulsion, our AI is dynamic, reactive, and interesting.

Spawn Patterns

This section is pretty technical, if you glaze over, skip here

When we were first pitching this game, I was imagining interesting movement patterns enemies would be doing as they flew into the stage. Each spawn pattern would be pre-choreographed and predictable, but since you’d typically have multiple spawn patterns playing at the same time, the ensuing chaos would make it more exciting and challenging… for the player that doesn’t actually exist.

I was confident I could execute on this vision, because all an enemy movement pattern needs is:

- A series of discrete points the enemy will move to.

- Curves between those points that the enemy will follow.

- The duration it will take to travel along that curve.

That’s just a Tween, and I love Tweens! In case you’re not aware, game developers use the word “Tween” to describe something that interpolates a variable from a set start to end value along a specified curve. That’s an overly technical, but precise and correct, definition. Essentially a tween works like this:

I have a vector called V which has the value {0,0}.

Move V to {300, 200}

-> following a quadratic curve

-> that starts fast and ends slow

-> over 3 seconds

(Caveat: “starts fast and ends slow” is sometimes called “ease in” … or is it “ease out”? I always get these confused, so I use more direct language)

What this will do is cause the vector V to have the value {300, 200} in 3 seconds, and in the meantime it will have a bunch of values in between such that it will start out very fast and then slow down as it approaches its destination. Don’t worry about the quadratic part, that just describes the specifics of how it will speed up and slow down.

There are some key things to note about this system:

-

Vis just some variable out in the ether, you can buckle something to its position, but there’s nothing inherently special aboutV. - You can do this to any variable that can be interpolated (basically anything represented with numbers, which is most things).

For the enemy ship movement I have something like this:

I have X and Y floating point values, each are {0}.

Simultaneously do the following:

Move X to {300}

-> following a quadratic curve

-> that starts fast and ends slow

-> over 3 seconds

Move Y to {200}

-> following a quadratic curve

-> that starts slow and ends fast

-> over 3 seconds.

Instead of moving a whole vector, I move each individual component at the same time. X starts fast and ends slow, and Y starts slow and ends fast. In the first example, despite that word “quadratic,” the actual observed motion is a straight line. In this example, the observed motion is more… curvy.

I could also flip this around and have Y start fast and X start slow, this will yield a similar, but different, result. If X starts fast then the ship will appear to move horizontally first and then adjust its vertical velocity. If Y starts first then it’s the opposite, moving vertically first and then adjusting horizontally.

Having all of these in my toolbox I can have an enemy movement pattern that’s like this:

MoveStraight(center)

MoveFastX(center + {100, 100})

MoveFastY(center)

MoveFastX(center + {-100, 100})

MoveFastY(center)

In just 5 lines of code I’ve choreographed a pretty interesting looking movement pattern. Add some Shoot() lines in there and we’re in business!

It was a little tricky to implement “shooting while moving” to this system but I did ultimately figure it out. Since I didn’t come up with it until pretty late in the project, not every enemy movement pattern takes advantage of this.

The All Nighter

GMTK 2023 was my 27th game jam (that’s the lower bound, it depends on how you count) this is far from my first rodeo. I have systems for how I manage time during game jams and I have rules that I don’t typically break. One of those rules is: always sleep. There’s a misconception that to be successful in a game jam you need to not sleep and code for 48 hours straight.

I’ve done 36 hour game jams where I got a comfortable 8 hours of sleep in the middle. When scoping out your game you should account for those secret 8, 16, or even 24 hours that will be banished to the dream dimension. Not only do I recommend sleeping during a game jam, I recommend trying to keep a semi-normal schedule. You’re more efficient when you’re well rested, so you should sleep the moment you start to feel tired.

So anyway I completely broke that rule for this jam.

Due to the timezone difference, the competition starts at 10AM on a Friday and ends at 10AM the following Sunday. This means if I am to sleep at a “regular time” Saturday night, I’ll have 2, maybe 3 hours to finish my game before I need to submit it at 10AM. That means the game needs to be basically done Saturday night. To make matters worse, Ryan and the artists had lots of in-flight work Sunday night that I’d need to implement first thing in the morning, burning whatever precious time I’d have.

There was simply not enough time to get everything in and also get a good night’s sleep. So I made a tough decision.

I have a strict caffeine regiment. I drink one cup of coffee in the morning, every morning, and then nothing else. Maybe I’ll have a decaf tea or coffee sometime before noon but I have a hard cutoff after that. That one cup of coffee is the backbone of my daily routine, it’s stayed consistent for me for pretty much my entire adult life.

At 12:05 AM, 8 hours to submission, I caught myself yawning. I took a deep breath, got up from my desk, and loaded up my espresso pot. This coffee ritual is all reflex, but it still felt weird doing it this late at night, like I was in some backwards dimension. Once I made the cup, I took it to my desk and didn’t drink it right away. Partly to wait for it to cool, but also partly because I wasn’t sure if I was ready to commit to what I was about to do.

One of my systems for game jams is to maintain a todo.txt file. For pest control, I organized the todo into sections for the major pillars of the game: Player AI, Enemy Wave Spawning, Player Mood, Interludes, and Art Asset Importing. Every time I had a new task to do, I’d add it to the todo under the appropriate section. The sections served as a reminder of what systems weren’t yet online. But once I had each feature 50% along it became more a matter of getting the highest priority thing done. So around this time I cut out all of the section headers and just turned it into a linear list. I started at the top and burned my way down.

Another adjustment I made at this time was turning off my computer clock. I don’t have any clocks in my house aside from my microwave and oven. So if I don’t look at my phone and can’t see my system time I can hide how long I’ve been awake from myself.

I was completely alert and awake the whole night. I don’t know if it was the coffee, the clarity of a prioritized task list, literally losing track of the time, or the unrelenting power of will to stay awake and finish this game. In that time I implemented the interlude system, wrote all the dialogue, brought all the remaining art assets into the game, implemented the player “mood” system (which was essential to the core loop), and implemented the boss fight. Things got cut along the way. But at this point in the project it’s more important to cross items off the list and sometimes that means scrapping them entirely.

Every few hours I would get up to use the bathroom and each time I would just sit there for a moment and close my eyes. I didn’t feel I was at risk of falling asleep, but it felt good to just rest my eyes and lower my head for a few seconds before I went back into the fray.

At 4:27 AM, 5 hours and 33 minutes before submission, I reached the bottom of the list. My commit message asked the question are we done?.

The answer was yes and no. The game was playable. But the very last item on the todo was, in all capital letters, “TUNING.” This meant making little adjustments to the spawn patterns, health values, player AI behavior, etc, to make sure the game is actually fun to play. This “TUNING” step was what really drove me to do the all-nighter. I could estimate how long it would take to get a new enemy type in the game, I couldn’t estimate how long it would take to tune the variables until the game was fun. So I spent 4 more hours tuning. This part is a blur. I can’t recall specifics of what I changed, but I’m pretty sure it was worth it.

11th hour Playtest

At 8:30 AM, 1 hour and 30 minutes before the submission deadline. I did a Discord screen share playtest. It’s important, (especially for a game jam!) to sit someone down in front of your game and just watch them play it. Say nothing, just watch and take notes. Did they understand your tutorial? Did they laugh at your joke? Are they engaged? Are they confused? Bored? All of these things are good data.

1 hour and 30 minutes isn’t really enough time to fix a totally busted game, but if the game is 80% there, a 20 minute playtest can help you find a low hanging 10% boost.

The good news is the playtester really liked the game. She said things like “this is very engaging” which I’ve learned from Bug Samurai that your game is not truly “fun” until a playtester says, out loud and unprompted, “this is fun.”

The one snag she hit was that she didn’t realize that putting the player in the “flow state” was what filled up the boss meter. I added one line of dialogue to the cold open to indicate this, and that was pretty much the final build.

After the submission deadline, submissions got extended by an hour (which they always do) because itch.io crashed (which it always does). Turns out 6,000 people all uploading large binaries to the same website simultaneously puts that site under some pretty heavy load, who knew!

Around 10:45 (15 minutes before the final, final deadline), Jose gave me some great feedback. I had posted the link in a Discord channel and he played it and sent back a bulleted list of his thoughts. This was where he said “I loved the cold open,” where you’re supposed to lose the first level before you actually learn how to play. I had mentioned to him that I was worried that players might accidentally beat the first level without losing first and get a weirder experience. He had suggested that I could turn off the boss meter on the first run to avoid this problem. That was a great idea, and it didn’t take that long to implement, but by the time I had it hooked up, it was 11:07, and the submissions were closed for real this time.

Takeaways

Here are the things I want to remember going forward from this jam.

- Get better at that “first contact” conversation with prospective teammates. Ask for portfolios, etc.

- Tweens are a very powerful tool. If it sounds like you can do it with Tweens, you probably can.

- AI is more about systems that coax the agent to go certain places over others, and less about any particular gameplay element

- All nighters are still bad, but GMTK feels way shorter than it is because of the awkward timezone change.

- Always playtest with real humans before you submit